Voyageur Technologique

Eternal Disagreements in Computer Science

Concepts which refuse to be nailed down

Differentiating concrete concepts from fuzzy categories is an essential step to mastering a domain. This took me years in Computer Science, because practitioners often deny categories are ambiguous. Thus, for all the noobs out there, here is a list of unanswerable questions. I’ve wasted hours of my life searching for definite answers to each of them. Whether to taboo these words or embrace their subjectivity is a personal choice. But at the very least, you should know that if someone claims to have an unassailable answer to any of these questions, they’re a gosh-darned liar.

What makes a language functional vs. object-oriented?

Functional languages

There’s a few attributes that make a language amenable to functional programming:

- Support for recursion (bonus points for Tail-Call Optimisation)

- Anonymous functions

- Closures

- Currying, which is also called partial application

- Lazy evaluation

- Functions as first-class data types

However, there is no definition of a “functional language”. Even Haskell, the most popular example of a functional language, behaves in a somewhat non-functional manner at IO boundaries. As discussed in the previously linked article, making a language “functional” is an ongoing area of research.

Object-Oriented languages

When people think about Object Oriented Programming (OOP), they typically think of Java. They imagine classes with private/public methods manipulating data, inheritance and interfaces. If they’re a bit more sophisticated they bring up SmallTalk as the original OOP language and cite Alan Kay’s definition:

OOP to me means only messaging, local retention and protection and hiding of state-process, and extreme late-binding of all things.

However, SmallTalk did not invent the term Object. Furthermore, what many consider one of the most essential parts of SmallTalk, late-binding via message-passing, isn’t really possible in Java. Thus, does that mean that Erlang is more Object Oriented than Java? Or maybe, as said by Hillel Wayne: “Terms evolve as problems do.”

OOP vs Functional

To summarize the two sections above in a pithy manner, here’s Hillel Wayne again:

What is the fastest language?

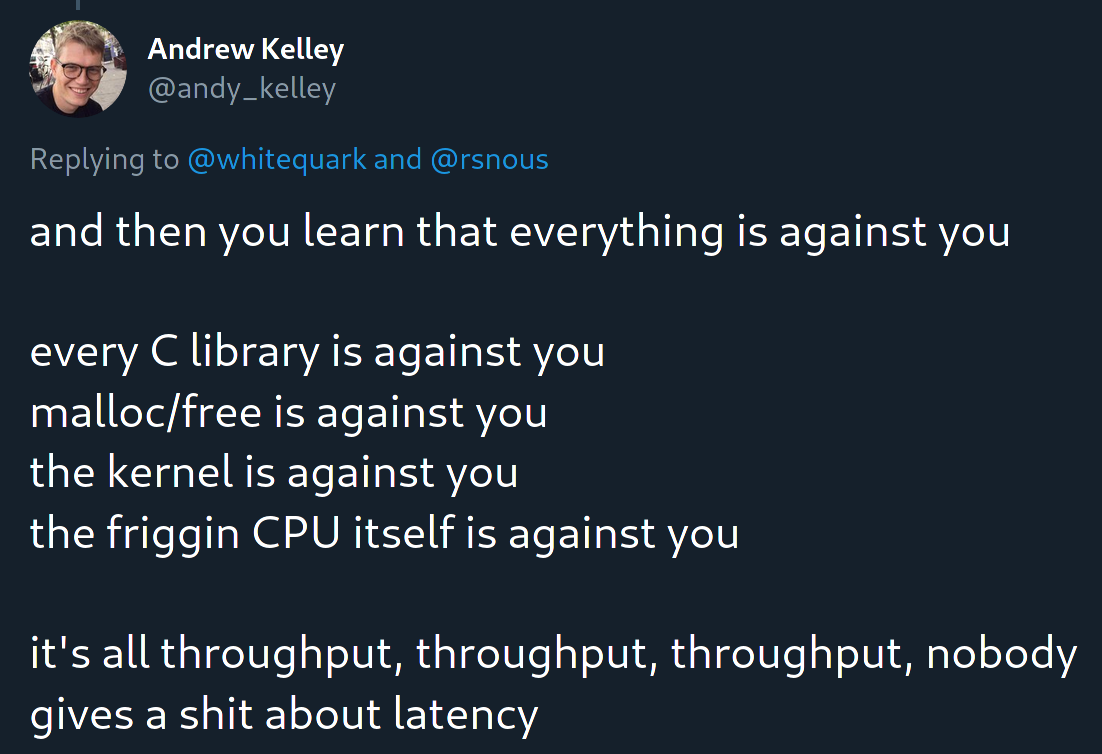

Well, C, but that’s only because we’ve spent decades tuning processors for it. But really which culture of programming are we talking about? Is it throughput or reactivity?

Because if we’re talking about throughput, Julia is much better than C at writing multi-machine, multi-GPU code. Alternatively, if you’re focused on reactivity, you have to start reckoning with the overhead added by various processor architectures and operating systems.

Eventually, you may start wondering if we were better off before all this complexity was added.

Anyways, yeah, properly written C is hard to beat, but not for the reasons typically mentioned. Are you sure you can’t use Zig instead?

What is the best language for teaching?

Every domain has its set of languages which battle for supremacy. Data Science is a constant battle between R, Python and Julia. Back-end web developers argue incessantly about the agility of Ruby on Rails and the speed of Go. Furthermore, new languages are constantly emerging from academia to change the landscape of what’s possible, so this paragraph is probably out of date by the time I’ve published it.

Ideally, teaching basic Computer Science concepts, such as functions and variables, should have found an agreed-upon language. However, as shown by the researchers of the Quorum language, very little empirical evidence has been collected on this problem. At the least, there does seem to be a consensus that static typing and Python-like (as opposed to C-like) syntax is helpful. These conclusions are so limited because collecting and analyzing empirical data about programming is super hard.

But maybe syntax and error messages are secondary to visualisation? After all, the first tool for understanding an algorithm is drawing it out. Tooling a language for visualization is called Projectional or Structured Editing. Allowing the manipulation of that visualisation to modify the code that generated it is called Bidirectional Manipulation, like Sketch-n-Sketch. All of these problems are incredibly challenging. Many people think this problem requires designing totally new languages and interfaces. Steven Krouse has made an excellent overview of previous attempts.

Consensus is overrated

The fact these concepts have no unified definition does not imply that Computer Science is a sham. It’s an indication that these aren’t the questions worth focusing on. They’re guide-posts towards something deeper.

Arguing about functional vs. OOP indicates a lack of historical awareness about their origins.

Debating “language speed” ignore the incentives and institutions (insurance and banking) that drove hardware development and how they might be changed.

Belief in an ideal language for teaching falsely assumes a perfect understand of why people learn to program and what cognitive tools they need.

All of these deeper questions are much harder to talk and reason about. I love these questions, yet I often find myself exhausted and overwhelmed when trying to engage with them. Advice on sustainably maintaining curiosity and joy is appreciated.

If you liked this article and want to read more discussions on Computer Science, consider subscribing to my mailing list.