Voyageur Technologique

Let Teens be Weird on the Internet

Teaching Security and Privacy in Schools

[epistemological status: I’m not a privacy or security expert. This post isn’t a thesis, it’s an essay by an amateur.]

Privacy is weird. Anyone who says it’s simple and straightforward, clearly isn’t using the Internet. Thanks to the rise of technology, it’s almost impossible to gauge accurately what privacy compromise (messing up your settings on a social media website) will result in a privacy catastrophe (somebody knowing something you REALLY didn’t want them to know about) later down the road. Given that it’s something ambiguous and difficult to grasp, somewhat like sexual health, it’s a great idea to teach in schools. However, I have a few issues with the current approaches.

1. Society is immutable, always right and always watching

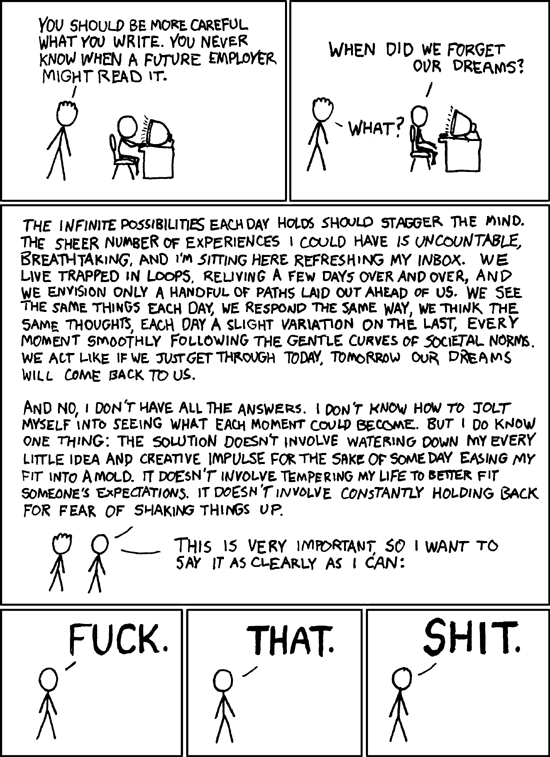

A lot of guides on Internet privacy and security aimed at school kids is the warning that anything they write can and will be used against them. On one hand, I understand the point they’re going for. Their audience is young, naive and the Internet is a really freaking permanent place. Consequently, I’m totally on board with the spirit of the initiatives, such as Binary Tattoo and THINK.

However, when I read materials on the subject, I find two assumptions are made. First, it’s impossible to be anonymous on the Internet. Second, society is right to judge you for anything you do out of line. This freaks me out a little.

The issue of anonymity is the easiest to address. You just need to educate kids about the basic ways people are usually identified online (IP addresses, location data and social give-aways mostly) and how more advanced ways are always being developed. Tell them that the best bet right now is Tor and explain how it works. Hell, send them my cringe-inducing YouTube Video on the topic. This way, if they want to do something creative and push the boundaries, they do it in a way that won’t be tracked. This is the same approach we take with safe-sex. We don’t want teens to be having sex, but if they’re going to have it, they might as well be safe about it. We don’t want teens to share angry poems or violent images, but since they’re going to, they might as well do it in a way that’s safe.

Obviously, Tor doesn’t solve everything. Talking about people you know and/or posting pictures/videos of yourself will immediately identify you. Which brings us to the second issue.

2. Leak victims are evil and worthy of eternal shame.

My primary problem with auto-shaming victims of leaks is it assumes consent. Most people with compromising photos on websites haven’t put them up themselves. Computers can be hacked, trust can be broken and images can be falsified using Photoshop.

Additionally, by victim-blaming the leak, it absolves the leaker and the reader of the leak of any responsibility. I find the best metaphor for this idea of responsibility is Cory Doctorow’s Knights of the Rainbow Hash Table: Everyone sucks at security. Attacks against security are becoming easier and easier. Everyone uses the Internet to connect. Consequently, everyone will get hacked and leaked in the future. Maybe it’s time to be responsible and not look at the leaks of your neighbours, just like you wouldn’t pick the locks to their doors when they’re not home? Maybe we should think of people who leak pictures and videos as criminals, just as we think of those who betray consent in other ways?

Instead of blaming victims of leaks for their predicament, I would rather if teachers taught about empathy. People make mistakes and intent shouldn’t be assumed. As John Green says, it’s important to imagine people complexly. Shaming, although becoming quite common given the Toxoplasma of Rage, shouldn’t be encouraged.

3. Privacy is sacred, except when the school takes it from you

Continuing with the metaphor of sex education, in some of the materials I read, privacy is talked about in the same tone as abstinence-only sex-ed talks about virginity; once you lose it, you can’t get it back and it’s super valuable.

In the context of the Internet, this isn’t totally inaccurate (see aforementioned permanence and naivete), but this idea gets weird when you realise that schools pay tons of money for custom firewalls. On top of that, the companies making the firewalls use the information gathered from students and the profits gathered from schools to make better firewalls to sell to autocrats and failed states.

And the icing on the cake is that firewalls don’t even work. Remember Tor? It goes around any firewall you can throw at it, including the Great Firewall of China.

This begs the question, if privacy so sacred, then why are schools investing money and effort to actively undermine it? What’s the alternative to invasive firewalls if we don’t want kids looking at bad stuff online?

Teach online ethics. Teach kids to talk to their parents or teachers if they find something they aren’t comfortable with online. Teach them to listen to that feeling of discomfort if they’re going deeper into something uncomfortable. Teach them to have enough self-confidence that if their friends are showing them something that doesn’t feel right, they can leave. Knowing your boundaries is important and acting upon them even more so.

4. The Internet is the only way your privacy can be compromised

A lot of the guides seem to miss the pervasiveness and legality of data collection. Your cellphone data is being sold. Your computer is probably spying on you, even if it’s operating system open-source.

This is a harder topic to talk about, since it’s much more nuanced, but I still think kids should be educated about the importance of open-source software, data should be emphasized as a liability, not a commodity and finally, the law shouldn’t be idealised, but shown to be flawed and unable to keep up with technological advances without citizen intervention.

In conclusion, I applaud those who make the effort to teach students about the Internet. It’s not an easy task. However, there are a few trends in the literature making me uncomfortable. I know we can do better.

If you liked this article and want to read more my posts on education, consider subscribing to my mailing list.