Voyageur Technologique

A Way Around the Coming Performance Walls: Neuromorphic Hardware with Spiking Neurons

[epistemic status: I work in a lab focused on computations with neurons, so I’m probably a little biased.]

Back in the day, when writing computing programs, you could always take comfort that even if your code had (non-exponential) bad performance Moore’s law would eventually save you from yourself.

This isn’t very true anymore. There are two coming performance walls coming to hit us. Worse still, there’s another wall one we’re already suffering from!

In this article, I’ll describe what these walls are, why they are such a problem and how neuromorphic hardware, especially those that work with spiking neurons, can offer a partial solution. I’ll also give a quick overview of the neuromorphic hardware my lab is developing as best as I understand it.

Moore’s Law, Amdahl’s Law and the Energy Efficiency Wall

Moore’s law is the idea that the transistor density of a chip doubles every two years, which means faster computers. However, what’s this has translated into for the last few years is pretty massively parallel architectures with a bunch of cores, because improving single core performance has hit a bit of a ceiling. So instead of super fast single processors, our processors have ridiculous amounts of sub-processors and we’re now looking to co-processors, like the GPU, for even further acceleration.

This means that now, more than ever, any code that you’re running serially instead of in parallel is going to be the bottle-neck. This is Amdahl’s law and it’s scary, because writing and compiling parallel code is hard.

But maybe we’ll get really good at writing parallel code? Unfortunately, we can’t even rely on Moore’s law to keep up. Moore’s law is ending for a wide variety of reasons including economic and physical, but worse still if we keep building processors as we traditionally do (this is called the Von Neumann architecture) we’re going to keep consuming more power.

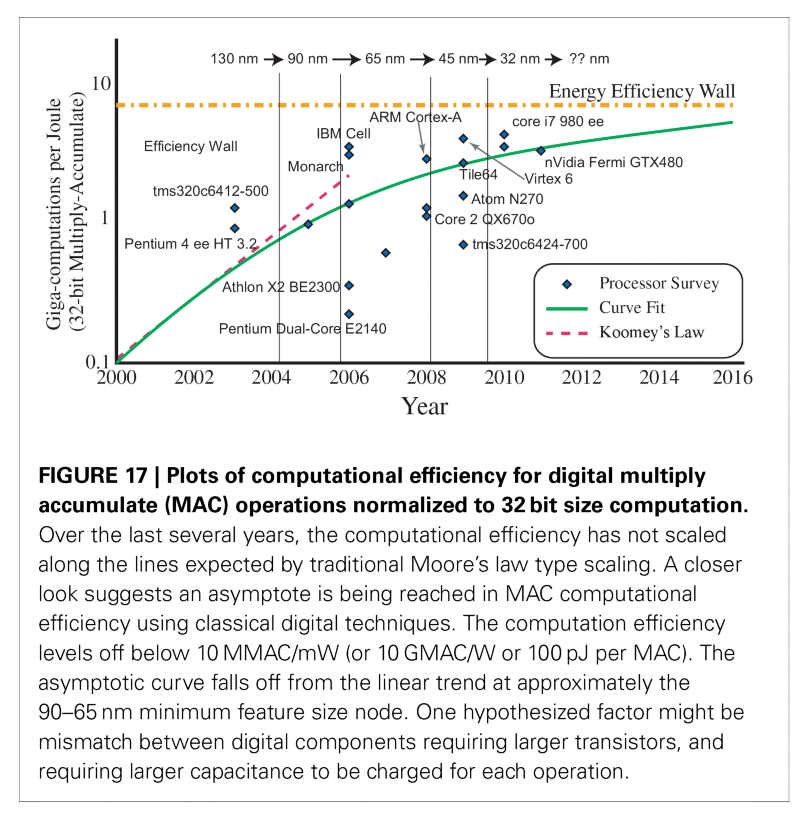

When I say the aforementioned traditional processors and their parallel co-processing brethren are power hungry, I’m talking specifically about how much power each calculation takes. It doesn’t look like it’s going to get any better any time soon. As you can see in the figure below, despite the fabrication process becoming more and more advanced over time (progressing from 130nm to ever smaller resolutions), the energy efficiency of their calculations isn’t increasing proportionately and we’re reaching an upper bound. This is called the Energy Efficiency Wall.

Neuromorphic Hardware

One of the hopeful new technologies that might lead us around the performance walls is neuromorphic hardware. Neuromorphic hardware is currently an exploding field, which is cool, but also super confusing. Basically, the idea is to make something like a neuron in silicon, because neurons are cool. I’m not being facetious here, the applicability of modern neuromorphic hardware is super variable. Ranging from TrueNorth, which can used trained (back-prop or RBM) feed-forward artificial neural networks, to Standfords Neurogrid, which used analogue neurons for biologically focused experiments. And then there’s this guy, who seems to at least have the marketing angle mastered?

One of the consistent optimizations that are happening across all these architectures, is that the memory is being placed closer to the processing unit. Like really close. Like chip-design level beside each other close. This saves a lot of power and a lot of time. So problem solved right? Except, now you have to be able to program these things. There’s a lot of interesting ideas around this. Some people think you’re just going to need to use the same old programming languages, but just use them more carefully. My lab thinks that a whole new approach is necessary using spiking neural networks that we design with Nengo.

Spiking Neurons and Nengo

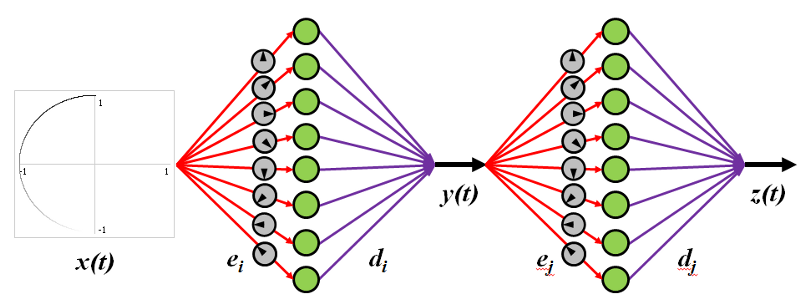

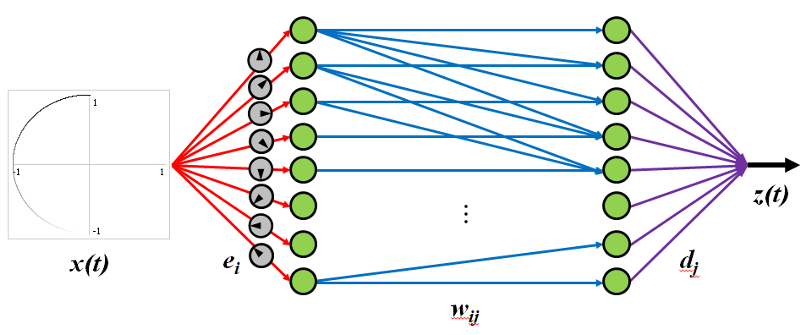

Nengo lets you compute in spiking neurons. Neuron groups approximate functions with non-linear encoders and linear decoders. Basically, thanks to neuroscience my lab’s figured out a way to go from the outside world to the distributed spiking world of neurons.

Encoders mean the non-linear weighted input into a neuron. This means neurons have a preferred direction that means they fire more when something that they are “tuned” for comes in. Notice in the GIF below that only certain neurons fire for certain directions, as indicated by the arrow direction in their grey circle.

To get back out of the distributed neuron world, all we need is decoders. Decoders are linear weights on the output of a neuron that get summed together to either recreate the original signal (the top circle) or an arbitrary non-linear function (the bottom figure-eight).

You can even chain decoders and encoders together to get the equivalent to a traditional all-neurons-interconnected neural network. Basically, you get all the benefits of neural networks without having to save a whole darn weight matrix.

With Nengo you can also do symbol-like and dynamic processing, as well as learning (both self-organising and error-driven) and combined all together you can build Spaun, the world’s largest functioning brain model. However, to explain all that stuff would take a book. All you need to know, is that Nengo let’s you define models of human-like behaviour in spiking neurons. A spiking neuron computational core allows for distributed (lots of neurons), asynchronous and parallel (neurons don’t wait) computing.

By the way, if you want non-GIF based, mathematical and methodical explanation of all this, check out the course notes to SYDE750 which covers all of this. If you want more of an “explorable explanation” type of thing, check out the Nengo GUI and work through the examples included.

Spiking Neuromorphic Hardware

Brainstorm is a chip being built by Stanford and my lab right now that harnesses all the things talked about in the last section. It uses analogue spiking neurons which have a few exciting benefits that results in a much lower power consumption for computation.

Firstly, a digital computer spends a lot of energy making sure it’s binary signals of “off” and “on” are never confused. As seen in the GIFs, analogue neurons distribute representation across neurons, so the accuracy doesn’t come from a single component, but from all the components working together.

Secondly, the hardware is completely asynchronous, just like the brain, which means low power and fast computational speeds.

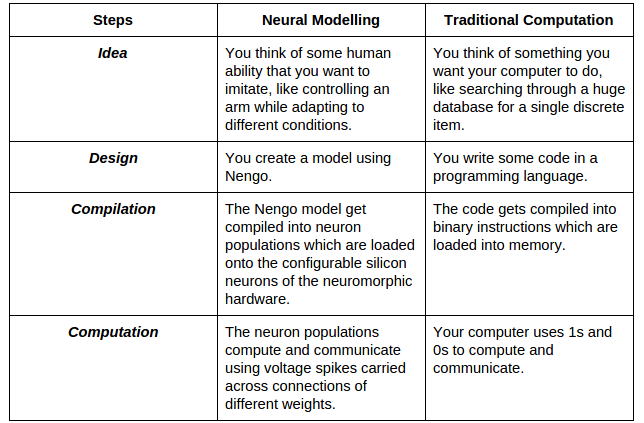

To review, let’s contrast the development process of Nengo models and traditional software.

Problem Solved?

In the end, I don’t think the Nengo is the “right” approach to the future of neuromorphic hardware, it’s just one of the first ones. Just like it’s the first one to make a guess at what computations the brain can do. For now, I’m happy to ride the thrilling wave of being first and I’ll be ecstatic when something else surpasses us.

I should also be clear that I don’t expect neuromorphic hardware to be the drop-in replacement of traditional computing hardware, at least not for a long time. I consider it more as an ambitious co-processor, to help out with things like control systems, computer vision and other tasks that humans excel at.

If you liked this article and want to read more of my brain science posts, consider subscribing to my mailing list.